Thirty years ago and old friend of mine by the name of Bill Tarplee was operating a magazine out of Canberra and he wrote a series of articles on buying, doing up and looking after hand tools. Bill was a manual arts teacher at one stage, very skilful with his hands and knows all that there is to know about hand tools (among other things). I have been lucky enough to secure his permission to republish some of his original articles and this is the third in this series.

It is interesting to see that of all the old fashioned hand tools, chisels have suffered most from modern fads. Consider for one moment that chisels, in one form or another, date back to the Stone Age. They have stood the tests of time through countless generations. The basic forms remained unchanged for hundreds of years, right up until the last 20 years that is. I do not know the reason for the change, but would guess that it is a combination of the loss of hand skills, and the “better looks” of just one chisel – the Bevelled Edge Firmer Chisel.

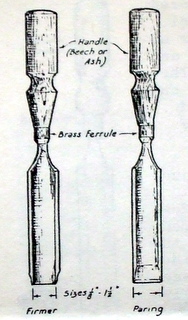

Up until recently the most common and widely used chisel was the firmer chisel, it is a solid (sometimes almost “block”) chisel. It had no ornaments or fine lines, but it did cut wood! For almost all day-to-day requirements it performed in a fine fashion. While it was designed for most of the normal jobs it did not have a fine blade for paring, nor an extremely heavy blade for the very heavy jobs sometimes encountered.

It is a tool that can be passed on for generations and one that is sometimes found with a blade sharpened almost back to the handle. It comprises of three parts – A blade, a handle and a ferrule to stop the blade tang from causing the handle to split.

To a large degree, the firmer has been replaced by the bevelled edge firmer. Where the firmer could be struck with a mallet, the bevelled edge was designed for lighter use where a mallet would not normally be required. It came into its own in paring (cutting across the grain) and in cleaning up the corners of holes cut into timber (usually called mortises). Because the edges were ground back at an angle, it could reach right into a corner without disturbing the sides of the mortise. As I said before, the bevelled edge has taken over. I suspect that this is because it looks better, and a lot of tools are bought by women who want “hubby” to be a bit more useful around the place. Which is not to denigrate the chisel, most of mine are bevelled.

The paring chisel is what might be considered as the extreme version of the bevelled edge chisel. Usually only found in specialised tool shops or as a “deceased estate” , they are both specialised and very useful – but only for light paring work. The original intention was for a chisel that would cut a clean cut across wood up to about 250mm wide. They should never be used with a mallet, as one glance at the ornamental handle will show.

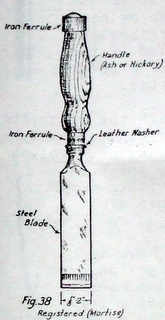

For medium heavy work, in conjunction with a mallet, one should use a registered mortise. It was designed for such use, with an iron or brass ferrule at both ends of the handle. As the name implies they were primarily used for mortises in hard timber, or where the mortise was of a reasonable depth. It must be kept firmly in mind that even with the registered; it was not designed for leverage.

Most chisels suffer abuse by users who insist on pulling the handle sideways, thus exerting considerable force on the blade, especially where it bears against the side of the mortise. The blade may show its displeasure at this treatment, and break.

If the chisel is properly sharpened and the operator knows a few basic points, such treatment is not necessary.

The only chisel I know of that was designed for extremely hard work, both with a mallet and as a lever, is the “socket mortise”. Unlike the other tools which rely upon a metal tang to secure the handle to the blade, the socket reverses the situation. In this case the blade is formed into a socket which the handle fits. This gives maximum strength. It was a tool that was designed for very heavy work such as wagon building, bridge work etc. Even in this instance the tool had to be sharp to work at maximum effectiveness. Again, they are becoming a tool that is increasingly rare. If you ever have the opportunity to buy either the socket or the registered at a reasonable pice I would advise you to do so.

One point – if you found a socket minus the handle, don’t pass it up. Most handles on old specimens wouldn’t be much good anyway as they were a “consumable” item. They can be easily replaced and could be made from any reasonable piece of hardwood that was filed up to fit. The metal ferrule at the top could be made from a short piece of galvanised water pipe or any other metal tubing (other than copper) that you had lying around the place.

Gouges are no more than curved firmer chisels. They are becoming increasingly rare, though I have bought several in the local markets. They are extremely useful in a limited way, and well worth buying if and when.....

Gouges can be divided into two classes – the Firmer (which is ground on the outer edge) and the Scribing (which is ground on the inner edge). I have it in my mind that they can also be called Incannelled (Scribing gouge) and Outcannelled (firmer gouge) though i can’t even find a reference to check the spelling on that.

Firmer are used for gouging with the grain, the scriber for paring across the grain. Generally they can be regarded as roughing out tools, as they are usually used to remove the bulk of the timber. Final smoothing up could be done with a very sharp specimen, though most craftsmen seem to use a set of specially shaped scrapers.

Grinding the firmer is simple, though you have to roll it across the face of the grinding wheel to get an even facet. It is sharpened on an oil stone in a similar manner. Sharpening the scriber required a curved face wheel, for the grinding and a slip (curved edge stone) for the sharpening. Needless to say, many were never sharpened properly.

Wood turning chisels are similar in shape, but mostly have a much longer blade and handle. They are of little use for normal hand woodworking as the extra length makes them very difficult to control on all but very limited jobs. However, at the right price......

Another form of curved chisels are carving tools. As a general rule these are both smaller and finer than the gouges and they cover a far wider range of shapes. They are extremely useful to have on hand for a wide range of paring and gouging jobs. I have had a set for years and while i have never used them for carving as such, still use them frequently. While one frequently sees of carvers beating sense into a carving chisel with a curved mallet, I’d have serious reservations about doing so to mine. The blades are far too thin and I doubt they would put up with that sort of treatment.

If from the foregoing you have gained the impression that i am against mallets (hammers and chisels are an unmentionable combination), you are dead right. It has been my experience that if the chisel won’t cut it is either too blunt or the grinding angle is too coarse. Personally, I would try both alternatives before I’d reach for a mallet. Anyway, that’s just a personal feeling.